Fans of Aickman tend to have a soft spot for the first of his stories they encountered, the one which ushered them into the heady territory of Aickmanland. For my money ‘The Hospice’ – my own personal gateway story – represents Aickman at his most unsettling, all the more so because it contains, on the surface, so little in the way of anything which appears to approach outright horror. Maybury, a travelling businessman, gets lost whilst driving through the outskirts of suburban Midlands and takes shelter in a remote hostel. Inside, seated in a dining hall of stale opulence, he is surrounded by seemingly doped-up guests and served mounds of indigestible food. Things take an disquieting twist when Maybury notices one of the guests is chained at the ankle to a radiator. The phrase ‘Kafkaesque’ is often used for shadowy and potent bureaucracy, but ‘The Hospice’ is Kafkaesque in that it evokes a nameless terror which is more abstract, and much more frightening, than anything as simple as a ghost.

The Cicerones (in The Unsettled Dust)

Frequently, the structure of Aickman’s stories involve an unassuming male protagonist stopping by somewhere remote and humdrum (or seemingly humdrum) and uncovering some disturbing and enigmatic hidden stratum of the world, as Freudian as it is supernatural. Here, a traveller visits the Cathedral of Saint Bavon in Belgium, intent on a brief look at a painting of Lazarus recommended by his guidebook. Inside he encounters a series of characters – the cicerones of the title – each of whom lead him deeper and deeper into the Cathedral, eventually into the crypt. Dense with symbolism and allusions, this is a story which touches on themes of religion, historicity, culture, and, ultimately, martyrdom.

Ringing the Changes (in Dark Entries)

Perhaps Aickman’s most famous story, ‘Ringing the Changes’ has been widely anthologised, including in the wonderful Roald Dahl’s Book of Ghost Stories, and it’s not difficult to see why. Gerald – another stiff-upper-lipped Englishman – takes his much younger wife on honeymoon to a remote coastal village where, from the off, a sense of gloom and dread hangs profoundly over them: they cannot see the sea; their hotel is populated with cryptic, unfriendly locals; and, all around, church bells endlessly ring out (asked why, one of the locals simply tells Maybury: ‘practice’). Worst of all is the reek of rot that seems to fog up from the pages as the story progresses, reaching its knockout effect in its rancid, unconscionable climax.

The Stains (in The Unsettled Dust)

This late story from Aickman – one of his last and one of his longest – won the 1981 British Fantasy Award for Best Short Fiction. It opens with Stephen, an old-fashioned civil servant and OBE whose predictable, traditional way of life begins to unravel when he finds himself newly widowed. Recuperating in the countryside he discovers Nell, a young, beautiful woman who could well be a woodland nymph, or an hallucination, or something else entirely. Their affair, at first blissful and passionate, is increasingly overshadowed by her father whose invisible presence prowls at the periphery of a story informed by weighty tensions: liberation versus repression, empire versus modernity, domestication versus freedom, civilization versus nature. If this all sounds a bit dully high-minded, it isn’t: rest assured that violent, terrifying dénouement will stay with you for a long time.

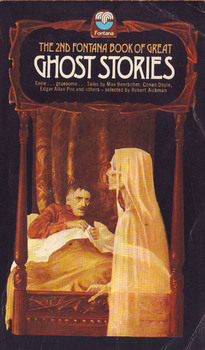

Fontana Introductions

Not an individual ghost story but a series of brief essays on the subject. For eight years Aickman edited and provided introductions for The Fontana Book of Ghost Stories series, accompanying his favourite tales with eloquent, incisive and eminently quotable observations about supernatural fiction, but also providing an Aickman reader with something of a divining rod for his own stories’ depths. Most importantly, these are strong, readable collections, including, alongside as a number of Aickman’s own stories, some of the lesser-known greats: Oliver Onions’ ‘The Beckoning Fair One’, Walter de la Mare’s ‘Seaton’s Aunt’, Algernon Blackwood’s ‘The Wendigo’.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed